Noiser

Everything You Need to Know About the Black Plague

Play Short History Of... The Black Death

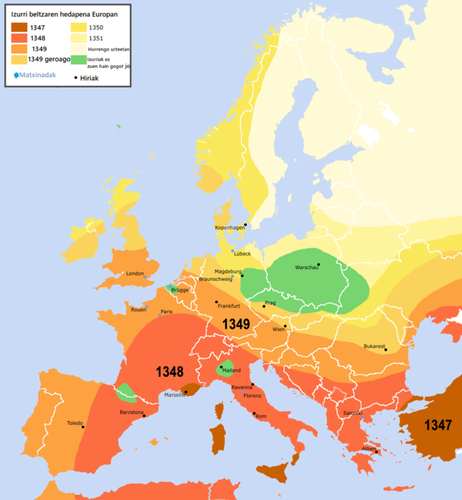

Lasting from 1346 to 1353, the Black Death killed around 60% of the European population. But where did it start? How did it spread? And how did it finally come to an end?

Where did the plague start?

Although no one can be sure, the outbreak likely began somewhere in Central Asia, perhaps in modern-day Kyrgyzstan, toward the beginning of the 1340s. From there, the Black Death swept through Asia, Africa, and Europe.

But bubonic plague, as it’s also known, was not a new disease. The “Great Pestilence” had been around for several thousand years, rearing its ugly head every few centuries or so. However, these earlier outbreaks did not travel with the same speed and virulence as the Black Death. So why was the Black Death different?

The plague itself had likely mutated, becoming more robust and transferable. Improved agriculture saw an explosion in the European population. More people, often not at peak health, lived closer together in unsanitary urban environments—ideal circumstances for the plague to rip through.

What were the symptoms?

Those infected with the black plague started with symptoms akin to the common flu: fever, headache, muscle soreness, chills. But as the virus ravaged through their bodies, they developed buboes, or painfully swollen lymph nodes. Contemporary witnesses said these buboes could swell to the size of an egg or even an apple. They were pretty unsightly, too, often leaking blood or pus. To make matters worse, people suffering from the plague usually got gangrene, which caused the tissue in the fingers and toes to turn black. This final symptom is thought to be why the plague came to be called the Black Death.

How did the Black Death spread?

The main way the Black Death spread initially was through fleas. These annoying little parasites liked to live in the fur of rats, who, in turn, liked to live in the bellies of trade ships.

In the 14th century, trade routes connected the world like never before. So-called “death ships” filled with sailors suffering from the plague started turning up at major ports, quickly infecting the cities. People fleeing these plague-stricken port towns carried the disease further inland.

Tremendous efforts were made to quell the spread of the disease. Some of the public health measures used today first emerged during the Black Death, including medical inspections, isolation of the sick, and quarantines. The term “quarantine” actually comes from the Italian word for 40—the number of days Venetian authorities isolated ships before allowing them to dock.

But not all these efforts were so forward-thinking. When there was no room left to dig more plague pits in Avignon, Pope Clement VI made the catastrophic decision to consecrate the River Rhône so that Christians might be buried in it. No thought was seemingly given to those who relied on the river for drinking and bathing water.

Were there any remedies?

As the plague ravaged the population, doctors across Europe scrambled to find remedies. However, with minimal medical knowledge, the “cures” they came up with were mostly ineffective and, in some cases, just made things worse.

In the mid-14th century, the medical community largely believed in the “miasma theory,” which posited that disease was spread through “bad air.” This bad air could emanate from anything, from misaligned planets to volcanic eruptions.

Doctors suggested people fumigate their homes with incense or smoke. People also began carrying bouquets of flowers or pouches of herbs and spices, which they held to their noses to fumigate the lungs directly. If bad smells made you ill, they argued, surely good smells could keep you healthy.

There were also several (utterly bizarre) cures involving animals. One suggested strapping a live chicken to a bubo to transfer the disease from the infected human to the bird. Another instructed one to chop up a snake and rub the pieces over the infected areas. The logic here was that the snake, as a symbol of the Devil, would draw the disease out of the body as evil was drawn to evil.

Potions and balms were also a popular, if ineffective, way of staving off the plague. One of the most sought-after was made from ground-up “unicorn horn.” This potion was very expensive, as it was believed that unicorns could only be lured out of hiding by virginal maidens and were thus very hard to catch. In reality, “unicorn potion” was probably made from narwhal tusks.

When did the Black Plague end?

The Black Plague effectively ended in 1353, but not before claiming the lives of an estimated 75–200 million people globally.

The practice of quarantining ships helped a great deal. And, after wiping out nearly a quarter of the human population, there were simply less hosts for the bacteria to spread through. The few people who remained had also likely developed some kind of immunity.

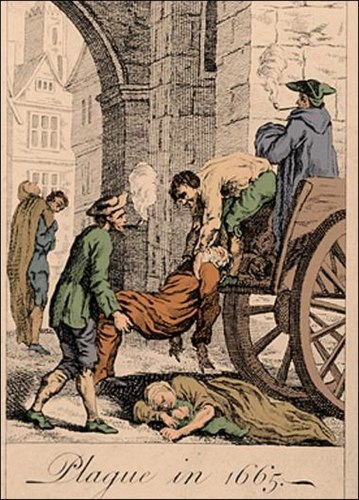

Even though the mortality rate had decreased, that didn’t mean the bubonic plague vanished entirely. Further deadly outbreaks occurred in the 17th and 19th centuries. The plague is even still around today, but thankfully, it can be easily treated with antibiotics if caught early.

Even though the mortality rate had decreased, that didn’t mean the bubonic plague vanished entirely. Further deadly outbreaks occurred in the 17th and 19th centuries. The plague is even still around today, but thankfully, it can be easily treated with antibiotics if caught early.