Noiser

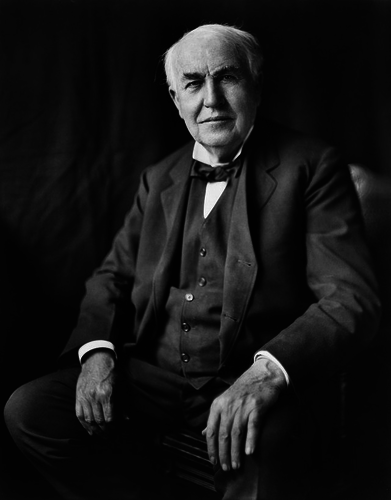

From Talking Dolls to Electric Cars: Thomas Edison's Lesser-Known Inventions

Play Short History Of... Thomas Edison

Today, Thomas Edison is known for groundbreaking inventions such as the light bulb, the phonograph, and the kinetoscope. But his most famous creations represent only a tiny portion of the staggering 1,093 patents the prolific inventor acquired throughout his life.

The Electric Pen That Led to Tattoo Guns

In the late 19th century, industries were booming in America like never before. It was an exciting time, but entering a new technological age had one very boring drawback: paperwork. Long before the invention of the photocopier, office workers had to handwrite memos and other important documents multiple times—a tedious and time-consuming task. Enter Edison’s electric pen. This nifty device, patented in 1876, was powered by a small electric motor and battery that pushed a needle up and down, as the employee wrote. Instead of ink, the electric pen produced tiny holes in wax paper, creating a kind of stencil of the user’s handwriting. The employee could then roll ink over the stencil and “print” their work on a blank piece of paper. Even though it was a good idea in theory, the electric pen never really took off: it was heavy, noisy, messy, and, above all, expensive. But this failed invention did leave an interesting legacy. In 1891, a tattoo artist in New York repurposed Edison’s design to create the world’s first-ever tattoo gun, forever changing the industry.

In the late 19th century, industries were booming in America like never before. It was an exciting time, but entering a new technological age had one very boring drawback: paperwork. Long before the invention of the photocopier, office workers had to handwrite memos and other important documents multiple times—a tedious and time-consuming task. Enter Edison’s electric pen. This nifty device, patented in 1876, was powered by a small electric motor and battery that pushed a needle up and down, as the employee wrote. Instead of ink, the electric pen produced tiny holes in wax paper, creating a kind of stencil of the user’s handwriting. The employee could then roll ink over the stencil and “print” their work on a blank piece of paper. Even though it was a good idea in theory, the electric pen never really took off: it was heavy, noisy, messy, and, above all, expensive. But this failed invention did leave an interesting legacy. In 1891, a tattoo artist in New York repurposed Edison’s design to create the world’s first-ever tattoo gun, forever changing the industry.

The World’s First Talking Doll

From Chucky to Annabelle, talking dolls have been the stuff of nightmares for decades, and we have Thomas Edison to thank for that. In 1877, Edison got the idea to miniaturise his phonograph and put it inside the chests of dolls. When cranked, each doll could play nursery rhymes like “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” and “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep.” The problem was that the wax records wore down after just a few uses, warping and distorting the recordings in disturbing ways. Children and adults alike were frightened by Edison’s toy, and they were discontinued after just one month of production. If you don’t feel like sleeping tonight, you can listen to the original doll recordings here.

From Chucky to Annabelle, talking dolls have been the stuff of nightmares for decades, and we have Thomas Edison to thank for that. In 1877, Edison got the idea to miniaturise his phonograph and put it inside the chests of dolls. When cranked, each doll could play nursery rhymes like “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” and “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep.” The problem was that the wax records wore down after just a few uses, warping and distorting the recordings in disturbing ways. Children and adults alike were frightened by Edison’s toy, and they were discontinued after just one month of production. If you don’t feel like sleeping tonight, you can listen to the original doll recordings here.

An Electric Car

At the start of the 20th century, battery-powered automobiles were growing in popularity. Gas-fuelled cars at the time were loud, vibrated, and produced a foul odour, while electric models had none of these disadvantages. Edison believed that electric cars were the future of automotive transport and, in 1910, created a reliable alkaline battery. Unfortunately, his work was soon overshadowed by his friend and former employee, Henry Ford, whose inexpensive Model T solidified combustion-engine cars as the dominant force in the automotive industry. Edison, however, was undeterred, designing and building three electric cars in 1912, though they never went into production.

At the start of the 20th century, battery-powered automobiles were growing in popularity. Gas-fuelled cars at the time were loud, vibrated, and produced a foul odour, while electric models had none of these disadvantages. Edison believed that electric cars were the future of automotive transport and, in 1910, created a reliable alkaline battery. Unfortunately, his work was soon overshadowed by his friend and former employee, Henry Ford, whose inexpensive Model T solidified combustion-engine cars as the dominant force in the automotive industry. Edison, however, was undeterred, designing and building three electric cars in 1912, though they never went into production.

Saying “Hello” When Answering the Phone

When Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876, he was immediately faced with a problem: what should someone say when answering his new-fangled machine? Today, it seems obvious that the answer is “hello,” but that wasn’t the case back in the 19th century. Originally, “hello” was used as a way to attract attention or express surprise, not as a greeting. Bell strongly believed that the traditional nautical salutation “ahoy” should be used when answering the phone, but Edison disagreed. When setting up a phone system in his office, he suggested using “hello” instead of “ahoy,” and the trend quickly caught on. Phone operating manuals across the United States adopted the word, and it’s been the standard telephone greeting ever since.

When Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876, he was immediately faced with a problem: what should someone say when answering his new-fangled machine? Today, it seems obvious that the answer is “hello,” but that wasn’t the case back in the 19th century. Originally, “hello” was used as a way to attract attention or express surprise, not as a greeting. Bell strongly believed that the traditional nautical salutation “ahoy” should be used when answering the phone, but Edison disagreed. When setting up a phone system in his office, he suggested using “hello” instead of “ahoy,” and the trend quickly caught on. Phone operating manuals across the United States adopted the word, and it’s been the standard telephone greeting ever since.

The World’s First Voting Machine

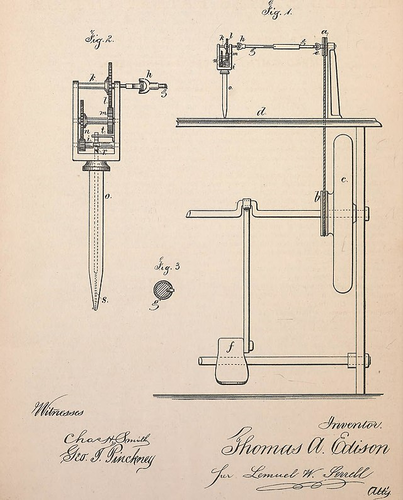

Thomas Edison’s first-ever patent was for a “vote recorder” that he envisioned would be used by legislative bodies like Congress. His invention worked brilliantly, automatically sending votes to a central recorder after legislators flicked either a “yes” or “no” switch. The problem was that elected officials hated the idea. After exhibiting it to a congressional committee in D.C., the chairman told a bright-eyed 21-year-old Edison: “If there is any invention on earth that we don't want down here, that is it.” You see, lawmakers liked the slow pace at which voting took place. It allowed them to discuss with their colleagues and potentially get them to change their minds. This experience taught Edison a valuable lesson: make sure your market wants what you intend to create.

Thomas Edison’s first-ever patent was for a “vote recorder” that he envisioned would be used by legislative bodies like Congress. His invention worked brilliantly, automatically sending votes to a central recorder after legislators flicked either a “yes” or “no” switch. The problem was that elected officials hated the idea. After exhibiting it to a congressional committee in D.C., the chairman told a bright-eyed 21-year-old Edison: “If there is any invention on earth that we don't want down here, that is it.” You see, lawmakers liked the slow pace at which voting took place. It allowed them to discuss with their colleagues and potentially get them to change their minds. This experience taught Edison a valuable lesson: make sure your market wants what you intend to create.