Noiser

How the Rosetta Stone Changed History

Play Short History Of... The Rosetta Stone

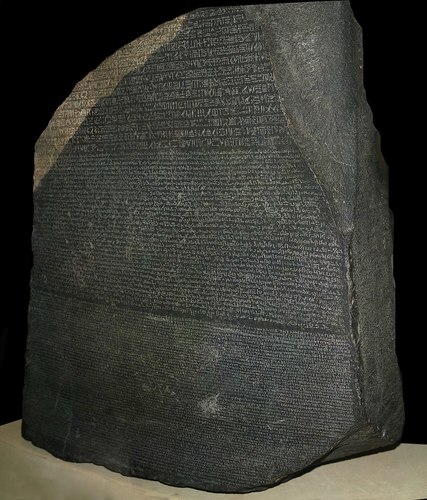

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous artefacts in the world. It is renowned not only for its historical significance but also for its pivotal role in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. But who made it and why?

The Discovery of the Stone

The Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799 during Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in Egypt. While constructing a fort on the banks of the River Nile, French engineer Pierre-François Bouchard unearthed a large, black stone slab covered in inscriptions. Recognising its potential importance, the soldiers transported the stone to Cairo to be examined by the French Institute of Scholars. Copies of the inscriptions were also made and sent back to universities in France for further study.

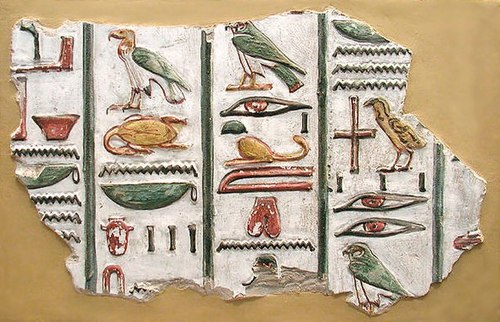

It quickly became apparent that this was no ordinary find—the Rosetta Stone bore the same text written in three different scripts: Greek, Demotic (a cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphics used in everyday life), and hieroglyphs (the formal script of ancient Egyptian priests and kings).

Egypt was a land of intrigue at the time of the Rosetta Stone's discovery. The French, eager to assert dominance both militarily and intellectually, sought to unravel the mysteries of Egypt's ancient heritage. The discovery of the Rosetta Stone intensified this scholarly pursuit, presenting a rare opportunity to solve one of Egyptology's most enduring puzzles: deciphering the mysterious hieroglyphs that adorned the country's temples and monuments.

However, just two years after the Stone's discovery, the French were defeated by the British. Under a treaty signed by a French general, a vast number of Egyptian treasures—including statues, maps, manuscripts, and other valuable artifacts—were surrendered to British forces. The Rosetta Stone was the jewel in the crown of this collection.

Decoding the Stone

One problem with the Rosetta Stone as an easy key to decipherment was that it was broken, so people couldn't easily match the three versions of the same text.

Richard Bruce Parkinson, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford

The race to decipher the Rosetta Stone became a fierce source of national pride between Britain and France. Both nations had brilliant scholars making significant progress, with English polymath Thomas Young making notable strides while Frenchman Jean-François Champollion emerged as his chief rival. Despite considerable progress on either side, Champollion finally cracked the code in 1822.

The Rosetta Stone's inscriptions date back to 196 BCE, during the reign of King Ptolemy V of Egypt. It's likely that the stone was originally part of a larger monument that stood in a temple.

All three inscriptions on the stone contain the same decree issued by Egyptian priests to affirm the divine status of Ptolemy V.

Champollion's breakthrough transformed the field of Egyptology. For the first time in centuries, scholars could read hieroglyphs, unlocking the ability to translate the countless inscriptions found on Egypt's temples, tombs, and monuments. This achievement opened the door to a far deeper understanding of ancient Egypt's history, culture, religion, and everyday life, shedding light on a civilisation that had long been shrouded in mystery.

In 1828, six years after his groundbreaking discovery, Champollion finally fulfilled a lifelong dream by visiting Egypt, the land that had fascinated him since childhood. This historic journey was transformative—not only for him but for Egyptology as a whole.

That is the moment many scholars would most like to have witnessed: when somebody enters Egypt and is able to understand its writings, in its own words, for the first time in thousands of years.

Richard Bruce Parkinson, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford

Sadly, Champollion died just two years after his trip to Egypt. In his last days, he urged his brother to continue to work on his book, which he dutifully did. The beautifully illustrated Grammar and Dictionary of Ancient Egyptian was published six years later. In light of his incredible achievements, Champollion became known as the father of Egyptology.

Impact

The Rosetta Stone has been on display in the British Museum since its arrival in England in 1802. Six million people visit the museum each year; for some, the Rosetta Stone is the item they most want to see.

It is now over two hundred years since Champollion made his breakthrough. Anniversary celebrations in 2022 were joyous, but they also raised an important question: is London the right place for this iconic exhibit?

Egyptian officials have argued that the Rosetta Stone is a vital part of their national heritage and that the artefact should be returned to its homeland. More than two and a half thousand archaeologists have signed a petition urging the stela to be returned to the country where it was inscribed and rediscovered. However, the British Museum says it has yet to receive a formal request for its return.

The significance of the Rosetta Stone is so bound up with its modern history, regrettable as colonialist modern history is, that it is hard to separate it from its journey into Europe. It belongs to the world, but it is also quintessentially Egyptian.

Richard Bruce Parkinson, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford