Noiser

Beatrix Potter's Forgotten Scientific Career

Play Short History Of... The Cuban Missile Crisis, Part 1 of 2

Before she became one of the best-selling children’s authors of all time, Beatrix Potter was a self-taught naturalist who made significant contributions to mushroom research.

A Born Naturalist

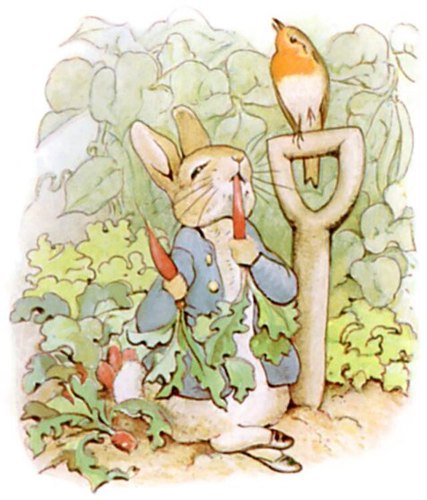

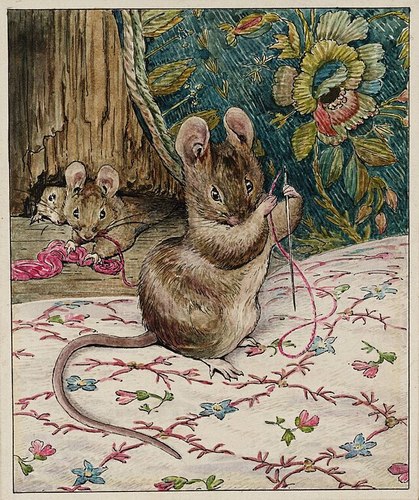

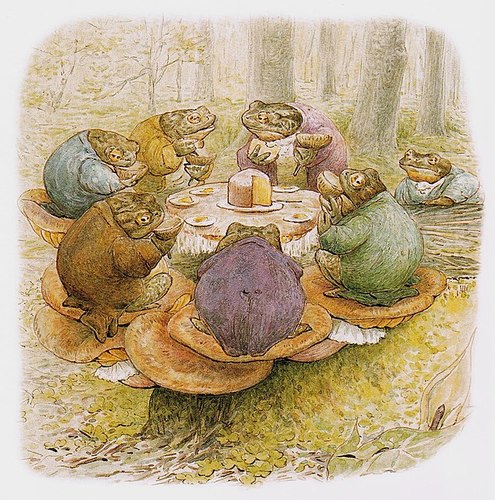

The works of Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) are notable for their delightful celebration of life’s minutiae. Her illustrations bristle with an appreciation for little things—bright-eyed dormice peer out of their earthen homes, rabbits munch delicately on crisp heads of lettuce, plump strawberries droop on dew-laden vines. The hyper-realism of Potter’s art makes the smartly cropped jackets and aprons her animals wear seem like an afterthought, added simply to create a sense of fantasy and whimsy. And perhaps they were, at least in part, because long before Beatrix Potter became one of the world’s best-selling children’s authors, she was a naturalist. Documenting the British Isles’ flora and fauna with scientific precision.

Beatrix’s interest in the natural world began in childhood. Like other wealthy Victorian families, the Potters would spend three months away each summer living in rented manor houses or county estates. During these retreats, she and her brother Bertram would roam the fields and forests collecting “specimens” for their nursery back in London. This room was soon filled with powdery butterfly wings, iridescent beetles, delicate snail shells, mushrooms, and small animals. Beatrix’s growing menagerie became the subject of her self-taught botany and biology lessons. Self-taught because Victorian women of her class were typically educated at home by governesses in topics like literature, language, music, and social and domestic skills. Mathematics and science were not prioritised in girls’ schooling.

Beatrix’s interest in the natural world began in childhood. Like other wealthy Victorian families, the Potters would spend three months away each summer living in rented manor houses or county estates. During these retreats, she and her brother Bertram would roam the fields and forests collecting “specimens” for their nursery back in London. This room was soon filled with powdery butterfly wings, iridescent beetles, delicate snail shells, mushrooms, and small animals. Beatrix’s growing menagerie became the subject of her self-taught botany and biology lessons. Self-taught because Victorian women of her class were typically educated at home by governesses in topics like literature, language, music, and social and domestic skills. Mathematics and science were not prioritised in girls’ schooling.

Scientific Contributions

A Victorian girl’s education was designed to make her a good, interesting wife—refined and charming but still skilled in household management. Beatrix, however, didn’t marry until much later in life, so spent her adult years honing her skills as an artist and scientist. In 1892, at the age of 26, she met and befriended Charles McIntosh, a revered naturalist and mycologist. Beatrix had always been fascinated with mushrooms—their vibrant colours, mysterious habits, and wild variation. But McIntosh encouraged her to go further in her studies, helping her with nomenclature, scientific classification, and microscopic techniques.

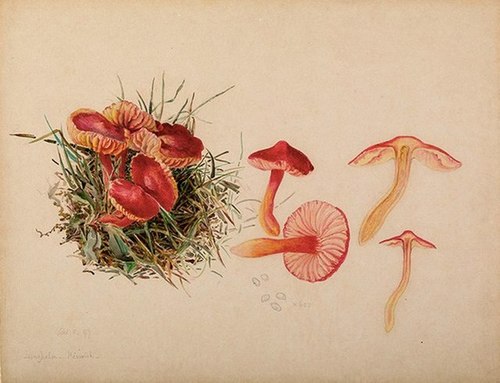

Her initial interest in fungi was because she thought they were such attractive shapes and colours. But as she drew them and learned a bit more about them, she became more and more interested in the actual science and the physiological science of what she was drawing.

Libby Joy, former chairman of the Beatrix Potter Society

The more Beatrix learnt about the strange and wonderful world of fungi, the more she realised how little was known about them. She became particularly fascinated with how they reproduced—a phenomenon that was not well understood in the 19th century. Beatrix began conducting her own experiments, germinating spores and observing them under her microscope. Based on this research, she wrote a paper, which she submitted to the eminent Linnean Society.

The Linnean Society was, however, very much a boy’s club. Women were barred from membership, naturally, but they also couldn’t access their research library or attend meetings. Upon reading her paper, William Turner Thiselton-Dyer, one of the society’s most distinguished members, crudely dismissed it as a “mare’s nest” of insignificant findings. After this encounter, a defiant Potter wrote in her diary: “I informed him that it would all be in the books in ten years, whether or no and departed giggling.”

From Rejection to Success

It turns out, Beatrix was right. Her theories on fungal spore germination were correct, and the illustrations she created of different mushroom species were so precise that mycologists consult them to this day. A century after dismissing her, the Linnean Society issued an apology stating that Potter "was treated scurvily by members of the society. The only consolation is that if she had become a scientist, she may never have written her books."

This may well be true, as "On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae" was her first and only academic paper. Shortly after, she began channelling all her efforts into her artistic pursuits and published The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1901. The book was an instant success, selling a staggering 20,000 copies in the first year alone.

Children across the globe have been captivated by Beatrix Potter’s body of work for over a century now. With one foot firmly planted in the realm of fantasy and the other in hyper-realistic naturalism, her stories continue to inspire new generations to discover the extraordinary world hidden in their own backyard.

Children across the globe have been captivated by Beatrix Potter’s body of work for over a century now. With one foot firmly planted in the realm of fantasy and the other in hyper-realistic naturalism, her stories continue to inspire new generations to discover the extraordinary world hidden in their own backyard.