Noiser

The Bone Wars: How an Intense Rivalry Helped Shape Palaeontology

Play Short History Of... The Dinosaur Rush

From public smear campaigns to outright sabotage, this is the story of how an epic rivalry between two amateur scientists laid the foundation for American palaeontology.

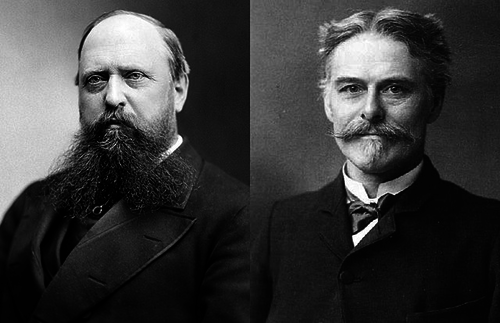

In 1870, a mere eight species of dinosaur had been unearthed in the United States. By the 1890s, that number ballooned to over 140. What triggered this sudden explosion of discovery? Well, believe it or not, it was an intense (and often petty) feud between two amateur palaeontologists: Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel C. Marsh.

From Friends to Enemies

Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel C. Marsh didn’t start off as enemies. In fact, you could even call them friends, united by their shared interest in palaeontology.

However, their relationship soured one fateful day in 1868 when Cope invited Marsh to a fossil quarry in Haddonfield, New Jersey. For Cope, this was a simple friendly gesture. Marsh, on the other hand, smelled an opportunity. He went behind Cope’s back and made an agreement with the quarry owner to send all fossils found at the site directly to his offices at Yale, effectively barring Cope from excavating there.

This move ended their friendship and kicked off one of the greatest rivalries in the history of science.

The Bone Wars Begin

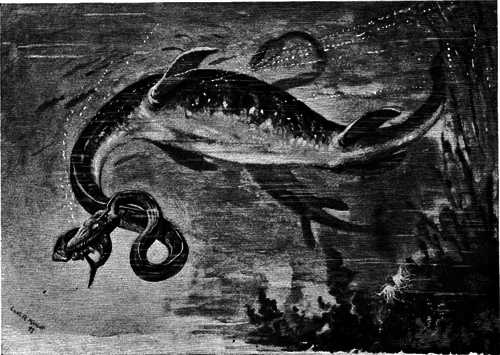

The first shots fired in the Bone Wars were fairly mild. In 1869, Cope named a small, slimy amphibian he discovered, Ptyonius marshii, after Marsh. Marsh countered the same year by dubbing what he believed was a “giant serpent”: Mosasaurus copeanus.

Their rivalry quickly escalated, however, when both scientists turned their attention to the fossil fields out west.

As the western territories were settled, farmers and railroad workers began unearthing fossils at an unprecedented rate. The opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 made it much easier for people to reach these remote areas—and you better believe that Marsh and Cope took advantage of it. As soon as word got to them about a new discovery, they’d race to the site to claim it as their own. They even paid those fortunate enough to stumble across fossil fields large amounts of money for exclusivity.

The tipsters led Marsh and Cope to three main sites: Morrison, Colorado; Canyon City, Colorado; and Como Bluff, Wyoming. These boneyards formed a golden triangle of palaeontology, and it’s here that the Dinosaur Rush really started in earnest.

Dirty Tricks

The digs were plagued by tit-for-tat dirty tricks, particularly at Como Bluff. Marsh had claimed this site, discovered by railway workers William Reed and William Carlin. But Cope began sending spies there and soon was able to persuade Reed to defect to his side.

Like Cope and Marsh, Reed and Carlin soon became bitter enemies, and the conflict reached new heights of pettiness. At one point, the diggers at the bluff loyal to Marsh threw rocks and dirt at Cope’s men. Worst of all, each side would often rebury or even destroy a site with dynamite once they were finished excavating to keep their opponents from finding any fossils they might have missed.

Despite the unprofessional behaviour, the digs in Colorado and Wyoming yielded extraordinary results, leading to the discovery of well-known dinosaurs like Triceratops, Diplodocus, and Allosaurus.

No Real Winners

As exciting as these discoveries were, dinosaur hunting was expensive. In the 1880s, both Cope and Marsh began burning through their considerable fortunes at an alarming rate. By the 1890s, neither could really afford to self-fund digs. But that doesn’t mean their rivalry ended.

They both launched respective smear campaigns against each other. Cope approached The New York Herald, offering an exclusive on the true nature of respected palaeontologist Othniel Marsh. Apparently, Cope had been compiling dirt on Marsh for years, obsessively storing it all in a drawer labelled ‘Marshiana’. The Herald took him up on his offer and, on January 12, 1892, published Cope’s scathing article. In it, he accused Marsh of plagiarism, stealing, and incompetence.

Of course, Marsh couldn’t let this stand. He quickly responded with a retaliation article titled “Wrong End Foremost,” in which he recalled Cope proudly showing him a reconstruction of a gigantic aquatic dinosaur called the Elasmosaurus back in 1869. The problem with this reconstruction, as Marsh snidely pointed out, was that Cope had placed the skull at the end of the animal's tail rather than its neck.

Cope and Marsh’s very public battle turned into a media circus, ultimately damaging both their reputations. Marsh still had some money left over to carry on with his work, but he was forced to live with the knowledge that he was more famous for his petty academic feud than his contribution to science. Cope, with his resources totally drained and unable to secure a prominent academic position, took a low-profile teaching job. On April 12th, 1897, he died following an illness. There were just six mourners at his funeral (not including his pet tortoise and gila monster, who were also in attendance). Marsh died two years later after contracting pneumonia.

Legacy

Though Marsh and Cope’s actions during the great Dinosaur Rush were certainly undignified, their work did leave a lasting impression on modern palaeontology. In the end, Marsh discovered a staggering 80 new dinosaur genera and species. Cope, 56. Even though they made an ultimately humiliating spectacle of themselves, said spectacle also got the general public excited about dinosaurs, which helped fuel further research in the field of palaeontology.

Still, in their rush to outdo one another, Cope and Marsh made quite a few mistakes, which palaeontologists are unpicking to this day. Their story serves as a reminder that scientific progress is best achieved through collaboration rather than competition.