Noiser

The Secret History of the Ninja

Play Short History Of... The Ninja

From films to comic books, ninjas have become some of the most recognisable cultural figures in the world. But who were the ninja really? Here is a fascinating look at the true story behind these legendary warrior spies.

Origins

The Ninja emerged in the 15th century during the Sengoku (Warring States) Period—a time of great political turmoil in Japan. The country had long been ruled by emperors of the Yamato clan, who claimed to be direct descendants of the sun goddess. But the Yamoto were puppet rulers—the real power lay in the hands of military dictators called the shogun, noble families, or Buddhist monks. By the middle 1400s, local lords called daimyo also started to establish decentralised kingdoms, adding to the complexity of the political environment. Amid the unrest, two regions found themselves in a unique position.

Iga and Koga lay close to the capital at Kyoto. They were geographically central to the turmoil, but their communities remained isolated and protected by a mountainous landscape. So the peasants of Iga and Koga were largely untroubled by bands of samurai mercenaries who roamed the land, violently forcing people in other regions to pledge allegiance to whichever daimyo the warriors served. Nevertheless, the villagers there soon realised that they must take steps to defend themselves. They refused to pay for the protection of the samurai and developed a unique fighting technique based on the ancient practice of shugendo, or the way of training and testing. An ancient ritual that dates back at least to the 7th century, shugendo focuses on physical and mental development.

Iga and Koga lay close to the capital at Kyoto. They were geographically central to the turmoil, but their communities remained isolated and protected by a mountainous landscape. So the peasants of Iga and Koga were largely untroubled by bands of samurai mercenaries who roamed the land, violently forcing people in other regions to pledge allegiance to whichever daimyo the warriors served. Nevertheless, the villagers there soon realised that they must take steps to defend themselves. They refused to pay for the protection of the samurai and developed a unique fighting technique based on the ancient practice of shugendo, or the way of training and testing. An ancient ritual that dates back at least to the 7th century, shugendo focuses on physical and mental development.

Shugendo was a practice of going to mountains, indulging in religious and physical self-improvement. They would go on marches to the mountains; they would sit under waterfalls; they would starve themselves; they would harden themselves. And this overlapped a good deal with the ninja techniques that were used for spying.

John Man, author of Ninja: A Thousand Years of the Shadow Warriors

The word ‘ninja’, however, would be meaningless to the people of Iga and Koga because it didn’t come into use until the 19th century. It means a person of perseverance or stealth, but the name they might give themselves was 'shinobi’, an older word meaning ‘one who sneaks’ or ‘conceals’. As both names suggest, the emphasis was on deception and secrecy—not violence.

Ninja vs. Samurai

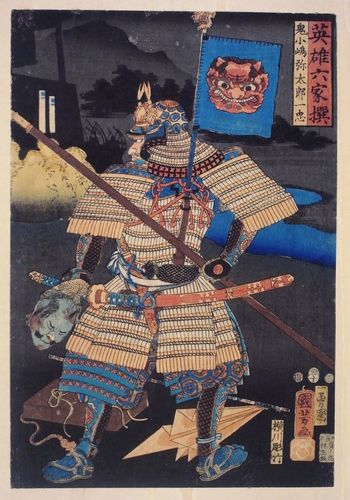

The two brands of Japanese warriors—the ninja and the samurai—are often confused, but there are many differences. Samurai were akin to mediaeval knights; they advertised themselves by wearing brightly coloured armour, often with identifying flags on their backs. They bristled with weapons and were bound by a strict code of conduct known as bushido. Etiquette held that a samurai should protect his honour by committing seppuku—a ritual form of suicide by disembowelment that proved his courage and self-control. A samurai might commit seppuku to atone for a mistake, to follow his master to death, or to prevent being captured by the enemy.

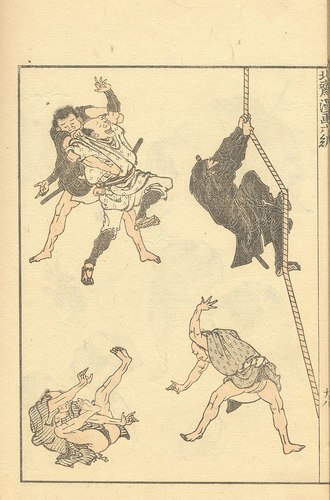

By contrast, the ninja were masters of survival. Their training allowed them to come and go without being seen—to fulfil their mission, escape, and live to fight another day. If samurai were soldiers, then ninja were spies. Many ninja were samurai, but very few samurai were also ninja—the “special ops” of Japanese warfare.

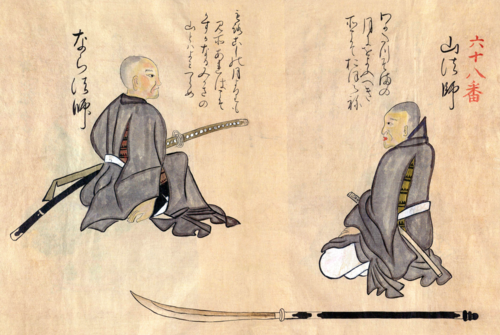

Another point of contrast to the brash samurai was the ninja’s attire, which was designed to blend in. For this reason, it is unlikely that they wore the familiar black robes depicted in popular culture because any kind of uniform would single them out. Instead, they preferred to hide in plain sight—perhaps disguised as monks, merchants, street performers, or the guards of the castle they were planning to infiltrate.

Another point of contrast to the brash samurai was the ninja’s attire, which was designed to blend in. For this reason, it is unlikely that they wore the familiar black robes depicted in popular culture because any kind of uniform would single them out. Instead, they preferred to hide in plain sight—perhaps disguised as monks, merchants, street performers, or the guards of the castle they were planning to infiltrate.

The Decline of the Ninja

In 1603, the Sengoku Period finally came to an end, and Japan was unified under the shogunate—a military government that ruled for over 250 years. This era, known as the Edo Period, ushered in a fundamental shift for the samurai and ninja alike.

Unification meant that the whole way of life in mediaeval Japan became redundant. Samurai became redundant. The only way that they could survive was by acting as servants to the government. The ninja, as far as they existed at all, were the police—basically secret agents—and they were supported in some way by the state. But that was their job. They were no longer ninjas.

John Man, author of Ninja: A Thousand Years of the Shadow Warriors

But the legend of the ninja continued to circulate and be celebrated. From the seventeenth century, there was a movement to preserve the knowledge of so-called ninjutsu skills, which were passed down by word of mouth. Books were produced—sometimes presented as manuals—that outlined the way of the ninja.

Legacy

Even though the true way of the ninja may have been lost, the necessity for their style of espionage only increased over the centuries and into the modern era. In 1937, Japan established the Nakano School, an elite training scheme designed to produce operatives to carry out sabotage, propaganda, and black ops. Graduates of the highly selective programme functioned outside the usual structure of the Army. In an era of Japanese imperialism, they were stationed overseas, working under cover in embassies or as journalists covering the war effort. Nakano School training drew on many historical approaches to warfare, including that of the mysterious shinobi.

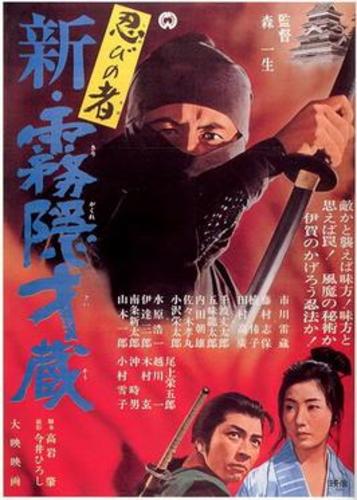

But more than anything, the Ninja endured as cultural icons. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a series of Japanese adventure books made the character of Sarutobi Sasuke, a Koga shinobi with almost supernatural powers, a household name. A second wave of popularity came in the mid-twentieth century, with the rise of cartoon books known as manga, which often depicted the historic heroism of the ancient ninja. It didn’t take long for the West to catch on, and ninjas began appearing in Hollywood films like the James Bond picture You Only Live Twice.

During these periods, the lines between truth and fiction were blurred almost beyond recognition. The black robes, superhuman powers, and gadgets like throwing stars were superimposed onto the real ninja.

This blending of myth and reality has led some to believe the ninja are figments of folklore, but history books show that ninja spies did exist—albeit in the margins. It is perhaps fitting that a group that prided itself on the utmost secrecy remains in the shadows even today.