Noiser

The Incredible Story of the Apollo 13 Disaster

Play Short History Of... Apollo 13

On April 13th, 1970, a catastrophic explosion aboard the Apollo 13 spacecraft spelt almost certain death for three astronauts. But somehow, against all odds, NASA was able to get everyone home alive. Here's the epic tale of how they did it.

Apollo 13

In 1961, at the height of the Space Race, President John F. Kennedy challenged the US to land on the Moon before the Soviet Union. Fifteen Saturn V rockets were contracted to meet this goal. However, only six were needed—this was the one Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins used on their successful 1969 Moon landing. With rockets to spare, NASA changed its mission goals—they'd use the extra rockets to refine space travel and gather scientific information from the Moon's surface. This was the purpose of the Apollo 13 mission.

Disaster Strikes

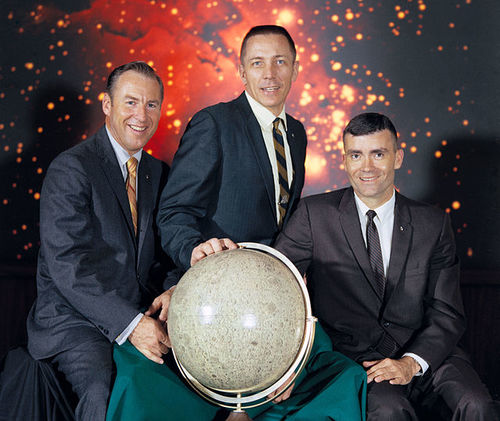

On April 13th, 1970, two days after launch, Apollo 13 was drifting 200,000 miles above planet Earth. Just as astronauts James Lovell, John Swigert, and Fred Haise were preparing to turn in for the night (a somewhat nebulous concept in space), a request was issued from central command. In Houston, Texas, ground control had been getting some odd readings from one of the liquid oxygen tanks, which provided breathable air for the crew. In zero gravity, the oxygen tended to settle, so each tank was fitted with a fan to stir up the contents when needed.

Swigert started the fans as instructed, not realising that one of the cryo tanks had a fatal flaw. Deep in the bowels of the spacecraft, a tiny spark was emitted from a faulty bit of wiring— harmless on Earth but enough to start a major fire in the oxygen-rich environment of the spacecraft. Less than two minutes later, the astronauts heard a loud bang, and the craft shuddered violently. Commander James Lovell voiced his concerns to Ground Control. ‘Houston,’ he told them, ‘We’ve had a problem.’

Swigert started the fans as instructed, not realising that one of the cryo tanks had a fatal flaw. Deep in the bowels of the spacecraft, a tiny spark was emitted from a faulty bit of wiring— harmless on Earth but enough to start a major fire in the oxygen-rich environment of the spacecraft. Less than two minutes later, the astronauts heard a loud bang, and the craft shuddered violently. Commander James Lovell voiced his concerns to Ground Control. ‘Houston,’ he told them, ‘We’ve had a problem.’

How do you fix a problem from 200,000 miles away?

In the Houston control room, Sy Liebergott, the Electrical, Environmental, and Consumables Manager, was responsible for determining exactly what Apollo 13’s problem was.

He started working on the problem of trying to figure out what had gone wrong and how to remedy the situation. As they tried things and moved forward through that problem-solving, it got worse and worse.

Ben Feist, historian at NASA and the creator of the interactive multimedia website Apollo 13 in Real Time

Ground Control began understanding the implications of the blown oxygen tank. The explosion took out a sizeable chunk of the service module attached to the command module, the astronauts were sitting in. Not only were oxygen levels flat-lining, but the fuel cells were also shutting down. The spacecraft was losing electrical power. Liebergott tried a series of fixes, but nothing worked. Eventually, he decided that the Moon landing would have to be abandoned.

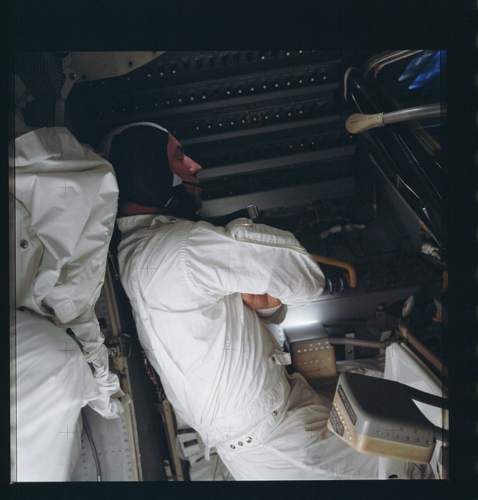

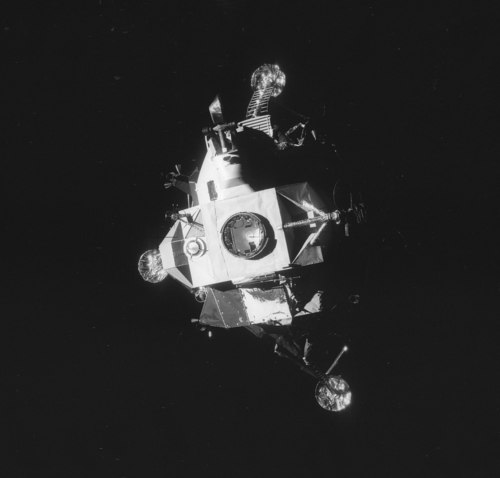

Power to the Command Module was rapidly failing, but the crew did have a lifeboat of sorts: the Lunar Module. The idea of using the LM (or 'Lem') in an emergency had been floating around NASA for some time. But no one had trained directly for this contingency, and no detailed strategy existed for how to do it. Plans were quickly cobbled together, and before long, one was locked in place. The astronauts would orbit the Moon and use its gravitational pull to slingshot them back to Earth. It was the stuff of science fiction, but would it work in real life?

Power to the Command Module was rapidly failing, but the crew did have a lifeboat of sorts: the Lunar Module. The idea of using the LM (or 'Lem') in an emergency had been floating around NASA for some time. But no one had trained directly for this contingency, and no detailed strategy existed for how to do it. Plans were quickly cobbled together, and before long, one was locked in place. The astronauts would orbit the Moon and use its gravitational pull to slingshot them back to Earth. It was the stuff of science fiction, but would it work in real life?

A Race Against Time

Lovell took command of the LM and piloted it through the blackness of space. To stretch their battery power out long enough to make it back to Earth, they needed to cut their electricity usage down to just 12 amps an hour—roughly what it takes to keep a pair of car headlights switched on.

Lights were extinguished. The computer was taken offline. The heating system was deactivated. The state-of-the-art lunar lander was now little more than a tin can drifting through space. The astronauts were in a desperate race against time. The precious little water they had had to be severely rationed for drinking and cooling the lander’s systems. Plus, with every breath the astronauts took, more toxic carbon dioxide filled the tiny space, threatening asphyxiation.

Lights were extinguished. The computer was taken offline. The heating system was deactivated. The state-of-the-art lunar lander was now little more than a tin can drifting through space. The astronauts were in a desperate race against time. The precious little water they had had to be severely rationed for drinking and cooling the lander’s systems. Plus, with every breath the astronauts took, more toxic carbon dioxide filled the tiny space, threatening asphyxiation.

There were always protocols in place for catastrophic mission accidents, which might involve very, very difficult decisions. For example, somebody giving their life to save the others.

Rob Godwin, author of Apollo 13, The NASA Mission Reports.

NASA spent a few hours designing a way to filter the carbon dioxide using the materials on board the lander.

It turns out the best way to do this was to combine some plastic bags with some duct tape, and I believe there was a sock involved as well. Essentially, what they were creating was some on-the-fly plumbing that would allow the airflow to go out of this round pipe into a square box and then back out into the spacecraft.

Rob Godwin, author of Apollo 13, The NASA Mission Reports.

But with one problem fixed, the next one emerged: re-entry.

Returning to Earth

Across America, more than 40 million people tuned into the live footage of the astronauts' re-entry. Millions more watched around the globe, across every time zone. In Vatican City, the Pope led prayers for the crew's safe return.

There were any number of things that could have gone wrong. The heat shield could have failed. The angle of re-entry could have been off. They could have failed at reducing the speed of the craft. All of these things might have resulted in instant death.

But, against incredible odds, Apollo 13 safely re-entered Earth's atmosphere on April 17, 1970. The world watched as the Command Module splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, just a few miles from its proposed landing site.

The men and women who worked in mission control were perfect in that moment. When the chips were down and they had to perform, they performed at the perfection level for human performance—at such a level that it warranted them receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom for their efforts.

Ben Feist, historian at NASA and the creator of the interactive multimedia website Apollo 13 in Real Time.